Wondering how to use technology in the classroom?

Check out this great site with links to hundreds of ideas

http://www.avatargeneration.com/2012/09/pinterest-boards-in-educational-technology/

Friday, October 12, 2012

Thursday, October 11, 2012

Want to know more on using computers with ESL students?

The Internet TSL Journal

iteslj.org/Techniques/AlKahtani-ComputerReading/

Using Technology to Help ESL/EFL Students Develop Language Skills

iteslj.org/Articles/Ybarra-Technology.html

Review

of the article: Implementing Language Acquisition in Classrooms

Introduction

‘Implementing Language

Acquisition in Classrooms’ was written by Richard P. Carrigan a former

administrator, in English Language Learning, at Milo Adventist Academy based in

Oregan. In this article, written in two

thousand and nine, Carrigan outlines a number of ways that ‘English as a Second

Language’ (ESL) students acquire language.

While his ideas are very relevant he appears to be unaware of the

benefits technology, specifically the use of computers.

Carrigan

Overview

Carrigan provides the reader

with a number of teaching methodologies to support the learning of ESL children

in the classroom. He introduces: the

idea of language absorption, fluency before accuracy, the order of language

acquisition skills and integrating student interests in to lesson

planning. Carrigan advises teachers to

provide safe learning environments and be aware of student’s feelings. Finally he warns against judging ability by

language output and stereotyping the ESL child.

Strengths and Weakness of

Implementing Language Acquisition in Classrooms

Carrigan article introduces

a number of ideas relevant to the teaching of ESL children. He stresses the importance of first knowing

English through listening. He refers to

this as language ‘absorption’. Carrigan

continues by introducing a number of methodologies for ESL teachers. He outlines the importance of communication

based classrooms that focus on expression of language rather than accuracy.

Carrigan presents the concept of ‘language in language out’ teaching that

“provides opportunities for learners to develop listening skills before

reading, reading skills before writing and writing before speaking” (Carrigan,

2009, p2). He encourages the use of

materials that are at an appropriate level and of interest to the learner. Teachers are urged to create safe places of

learning where students feel free to try without fear of failure (Carrigan,

2009, p3). Carrigan builds an awareness

of the ESL student’s emotional needs that begin with excitement and soon give

way to despair and frustration. Teachers are further warned to be aware of

their body language and general comments and to avoid stereotyping.

While Carrigan has raised

some relevant and very useful ideas it is surprising that he has omitted the

potential of Computer Assisted Instruction (CAI) with ESL students (Ybarra

& Green, 2003, p1). Computers have

been shown to motivate and “maintain learner focus, stimulate problem solving,

anchor discourse, and encourage learner directed talk and action” (Meskill,

2005, p55). In short, they are an

excellent resource for encouraging verbal exchange. Ybarra and Green (2003) note the varied

verbal interactions between ESL students using computers, these include: making

commands, sharing opinions, suggestions, asking questions and giving responses (p2). Computers may provide immediate feedback,

added practise, increased interaction with texts and improved comprehension

(Ybarra & Green, 2003, p3).

Conclusion

Carrigan’s article is a

useful resource for creating an awareness of ESL methodologies and the needs of

the ESL student. However, it is

important that teachers acquire a variety of teaching methodologies and remain

at the forefront of teaching innovations and research. The use of computers in education and their

benefits to ESL learning must not be ignored.

References

Carrigan,

R. P. (2009). Implementing Language Acquisition in Classrooms. The Education Digest, 75(4), 57-61 [Electronic

version]. Retrieved from: http://search.proquest.com.databases.avondale.edu.au/docview/21

Meskill,

C. (2005). Triadic Scaffolds: Tools for Teaching English Language Learners with

Computers. Language Learning and

Technology [Electronic version]. Retrieved from: http://II.msu.edu/vol9num1/meskill/

Ybarra,

R., Green, T. (2003). Using Technology to Help ESL/EFL Students to Develop

Language Skills. The Internet TESL

Journal, 9(3), [Electronic version]. Retrieved from:

iteslj.org/Articles/Ybarra-Technology.html

Access Strategies For Computing

The provision of computers

is no longer an option; it is a necessity.

Stager states, “We must respect the role they can play in children’s

lives and develop ways to maximize the potential of technology” (Stager, 2005,

p2). Therefore, schools must evaluate

the technology available to them and its potential for maximising access for

all students. Options include:

Interactive whiteboards, classroom performance systems, stand-alone computers,

computer banks, computer suites, laptop trollies and one-to-one laptops.

Interactive Whiteboards (IW)

and Classroom Performance systems (CPS) are two alternatives for providing

technology access in the classroom. Whiteboards may engage students in learning

and enhance the learning experience; provided they are used as interactive whiteboards and not just as

another form of chalkboard. A creative

teacher might also plan small group activities that involve the use of the

interactive whiteboard. Stager warns

against using an interactive whiteboard to “reinforce the dominance of the

front of the room and omniscience of the teacher” (Stager, 2006, p5). Classroom Performance Systems while novel are

limiting. They do little to encourage

children to embrace computer technology (Stager, 2006, p5).

One or two computers in a

classroom may provide limited access to technology. Computer usage would need to be carefully

scheduled, perhaps including break times, to allow for maximum exposure and

equity for all children (Gahala, 2001, p2).

One or two computers, while useful, are not the ideal. With thirty children in the average Primary

Classroom, a long time would pass between rotations even if the children worked

in pairs. Small group instruction would

be difficult with six children crowded around a small screen. Opening the classroom for extended computer

use would mean extra duties for the teacher.

Clearly, if it is within the school budget, computer banks within the

classroom would be more suitable.

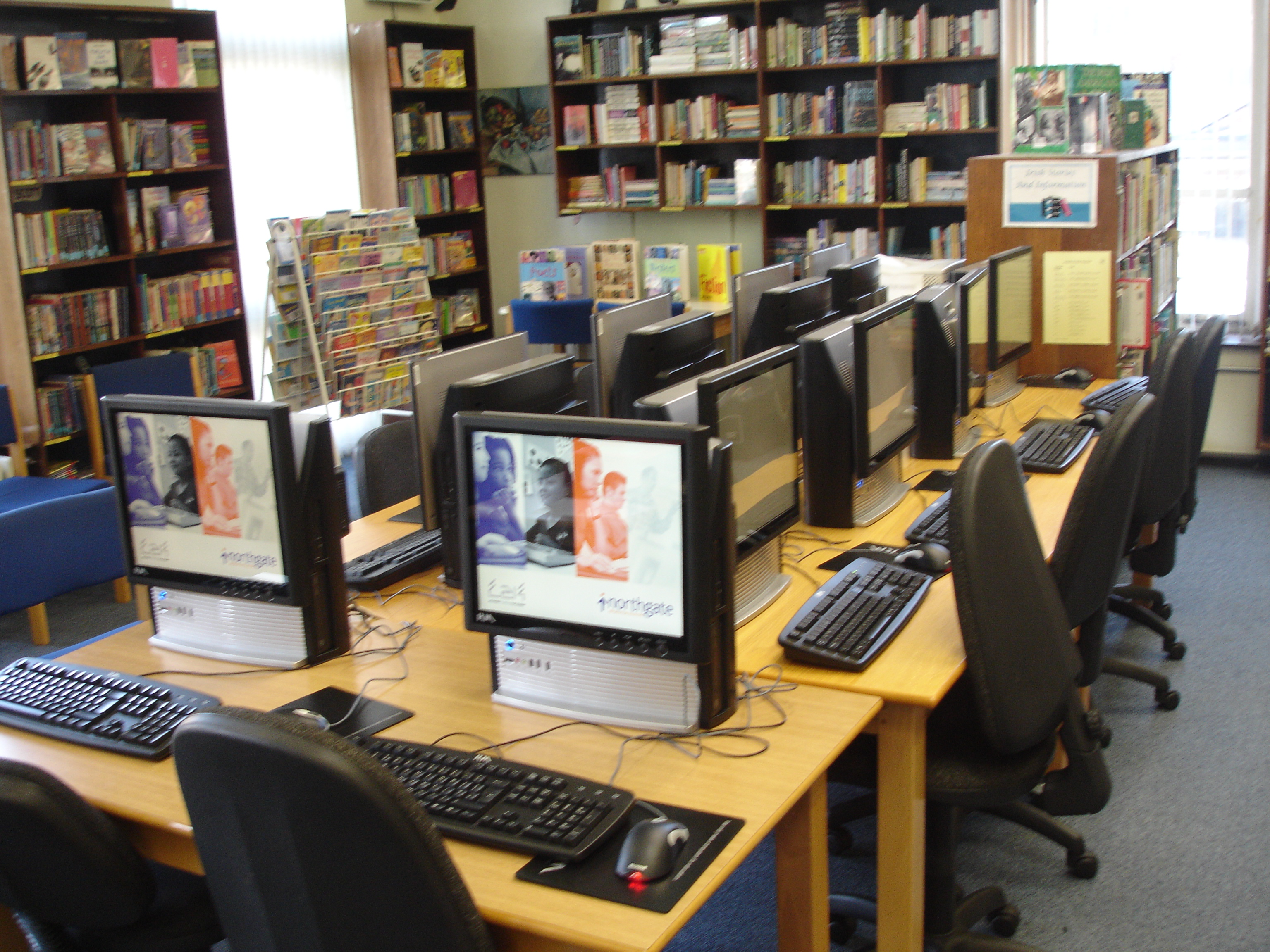

Computer banks of six to

eight computers would have a greater impact, providing access for a larger

number of children at one time. Computer

banks enable the teacher to plan for rotating small group activities allowing

children to experience technology on a more regular basis and perhaps for a

longer period of time (Strategies for Allocating Computers, 2012). With several children working at the same

task the students may support each other when difficulties arise. Computer banks while a better alternative to

single computers have their disadvantages.

Classrooms with thirty children have limited space and wiring for

computers is expensive. Teachers also

need to be proficient with computer applications to ensure that groups are able

to work independently.

Computers that are set up

within a separate area such as the library, a lab or suite are a further option

for computer access. Wiring of one area

is a cheaper option to a number of classrooms over a large area. Labs may provide access to all students

before and after school and at lunchtime, however, this would again mean extra duties

for teachers. Having the computers in

one area may also be a disadvantage as staff may not feel the need to integrate

computers into their class curriculums.

Gahala states that using computers in a lab “may be a barrier to using

them on a continual basis as a part of the curriculum” (2001, p2).

Laptop computers in either

mobile trollies or as one-to-one computers are the ideal. Mobile laptop trolleys may be used to store

and recharge the laptops when not in use.

Laptops are easily transported into a variety of settings and may be used

for a small group or whole class depending on the activity (Stager, 1998, p1). Laptops take up less space and can be stored

in an area away from the classroom (Gahala, 2001, p2). They are a “cost effective alternative to

building computer labs, buying special furniture and installing costly wiring”

(Stager, 1998, p1). Furthermore they increase

student engagement and alleviate behaviour problems associated with more

traditional teaching styles (Hu, 2007, p3, Bustamante, 2007, p3). Laptops, however, are an expensive set of

equipment and while portable laptop trollies may suit some schools the terrain

in others may make them difficult to manoeuvre.

Laptops that remain only in the school domain do not allow children the

time to explore and are not able to be utilised for homework.

For maximum access to

computers students require one-to-one laptops that travel everywhere with them

and are not bound to the confines of the school. “These computers need to be the students’

constant companions, as accessible, as ever-ready, as a carpenter’s hammer”

(Barker, 2007, p1). Individual laptops

become an extension of the child enabling him/her to explore, create, collect

and collaborate (Stager, 1998, p1, Stager, 2003, p1). Knowing that students have one-to-one access

allows teachers the freedom to plan the curriculum using technology. With laptops learning may extend beyond

school hours and technology is easily integrated into homework tasks. Maintenance and repairs may be costly and

this would need to be factored into the school budget. Prior to introduction adequate fire walls and

policies on acceptable use would need to be in place to ensure the safety of

the children.

Although one-to-one laptops

are the best solution for high access unfortunately the monetary cost of

technology and its continual maintenance makes the one-to-one program beyond

the reach of many schools. A school

would do well to consider an incremental roll out of banks of six laptops

starting with the classrooms of teachers who are enthusiastic about technology. Laptops could be linked to a server and

wireless access points set up around the school to enable internet access in

all areas. Teacher and student files

may be stored on the server allowing for greater storage. During the incremental roll out a plan should

also be formulated for the future introduction of one-to-one laptops and

ongoing staff training.

References

Barker,

G. (2007, September 13). Logging into the laptop revolution, Sydney Morning Herald [Electronic

version]. Retrieved from www.smh.com.au/small-business/logging-into-the-laptop-revolution-20090619-cptx.html

Bustamante,

C. (2007, May 4). Laptop program missing keys. The Press Enterprise [Electronic version]. Retrieved from Avondale College Moodle, EDUC32400, Issues in

Educational Computing: Laptop_program_missing_keys (3)

Gahala,

J. (2001). Critical Issue: Promoting Technology Use in Schools. North Central Regional Educational

Laboratory [Electronic version]. Retrieved from Avondale College Moodle,

EDUC32400, Issues in Educational Computing: Critical_Issue_Promoting_Technology_Use_in_Schools

(2)

Hu, W.

(2007, May 4). Seeing No Progress, Some Schools Drop Laptops. The New York Times [Electronic version].

Retrieved from Avondale College Moodle, EDUC32400, Issues in Educational

Computing: Seeing_No_Progress_Some_Schools_Drop_Laptops_-_New_York_Times

(2)

Stager,

G. S. (1998). Laptops and Learning Can laptop computers put the “C” (for

constructionism) in Learning? Gary S.

Stager Support for Progressive Educators [Electronic version]. Retrieved

from Avondale College Moodle, EDUC32400, Issues in Educational Computing:

Laptops_and_Learning

(2)

Stager,

G. S. (2003). School Laptops - Reinventing the Slate. Gary S. Stager Support for Progressive Educators [Electronic

version]. Retrieved from Avondale College Moodle, EDUC32400, Issues in

Educational Computing: Reinventing_the_Slate (3)

Stager,

G. S. (2005). The High Cost of

Incrementalism in Educational Technology Implementation. (World Conference

on Computers in Education, Stellenbosch, South Africa) (Electronic version). Retrieved

from Avondale College Moodle, EDUC32400, Issues in Educational Computing:

incrementalism

(2)

Stager,

G. S. (2006) Has Educational Computing

Jumped the Shark? (ACEC 2006 – Cairns Australia – October 2, 2006)

[Electronic version]. Retrieved from Avondale College Moodle, EDUC32400, Issues

in Educational Computing: ACEC_2006_Paper_-_Gary_Stager (2)

Strategies for Allocating Computers [Electronic version]. (2012). Retrieved from Avondale

College Moodle, EDUC32400, Issues in Educational Computing: Strategies_for_Allocating_Computers

(2)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)